Trailer

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tn_2Ie_jtX8

Soundtrack

Storyline

<p>Ishaan is an 8-year-old boy living in , who has trouble following school. He is assumed by all to simply hate learning and deemed a troublemaker, and is belittled for it. He has even repeated the due to his academic failures from the previous year. Ishaan’s imagination, creativity and talent for art and painting are often disregarded. Ishaan’s father, Nandkishore Awasthi, is a successful executive who expects his sons to excel and his mother, Maya, is a homemaker who gave up her career and is frustrated by her inability to educate Ishaan. His elder brother Yohaan is an exemplary student and tennis player in whose shadow Ishaan remains, though he is the most supportive of Ishaan. One day after Ishaan school, his parents are called by the principal to discuss his behavior and grades. Due to Ishaan’s failures, lack of improvement and rebellious behavior, the principal suggests they look into special schools, but Nandkishore rejects this and sends him to a despite Maya and Yohaan’s protests. Alone there, Ishaan rapidly sinks into a state of fear, anxiety and , which is only worsened by the teachers’ strict and abusive regime. Ishaan’s only friend is Rajan Damodaran, a physically disabled boy who is one of the top students and resides with his family there, as his father is part of the school’s board. Ishaan contemplates suicide one day, but Rajan intervenes and stops him. Rajan subsequently informs Ishaan that Mr. Holkar, the boarding school’s strict and abusive art teacher, has left and is being replaced by someone else. Ram Shankar Nikumbh, a young, cheerful and optimistic instructor at the Tulips School for young children with , joins as the boarding school’s temporary art teacher the same day, replacing Mr. Holkar. Ram’s teaching style is markedly different from Holkar’s, and he quickly notes Ishaan’s unhappiness after Ishaan fails to draw anything during the class. Ram reviews Ishaan’s work and concludes that his academic shortcomings are indicative of . Ram then visits Ishaan’s house in Mumbai, where he is surprised to discover Ishaan’s hidden interest in art. Ram demonstrates to Maya and Yohaan how Ishaan has extreme difficulty in understanding letters and words due to dyslexia and his trouble in sports stems from his poor motor ability (which also applies to his difficulty in tying shoelaces and judging the size, speed and distance of a ball). However, Nandkishore labels it as an intellectual disability (as well as an excuse) and dismisses it as laziness, much to Ram’s frustration. Back at school, Ram brings up the topic of dyslexia in a class by offering a . Ram comforts Ishaan, telling him how he struggled as a child as well. Ram obtains the principal’s permission to become Ishaan’s tutor. With gradual care, Ram works to improve Ishaan’s reading and writing by using developed by dyslexia specialists. Eventually, both Ishaan’s demeanor and grades improve. One day, Nandkishore visits the school and tells Ram that he and Maya have read up on dyslexia and understand the condition. Ram mentions that what Ishaan needs more than understanding is that someone loves him. Outside, Nandkishore sees Ishaan attempting to read from a board. With teary eyes, he is unable to face his son and walks away, remorseful. At the end of the school year, Ram organises an arts and crafts contest for the staff and students, judged by artist . Ishaan’s work makes him the winner and Ram, who paints Ishaan’s portrait, is declared the runner-up. The principal announces that Ram has been hired as the boarding school’s permanent art teacher. When Ishaan’s parents meet his teachers on the last day of school, they are left speechless by the transformation within their son. Overcome with emotion, Nandkishore thanks Ram. Before leaving, Ishaan runs toward Ram, who lifts him high up in a hug, advising him to come back next year. The husband and wife team of and Deepa Bhatia developed the story that eventually became as a way of understanding why some children could not conform to a conventional educational system. Their work began as a short story that evolved into a screenplay over seven years. Bhatia said in an interview with that her original inspiration was the childhood of Japanese filmmaker , who did poorly in school. She cited a specific place in Kurosawa’s biography where he began to excel after meeting an attentive art teacher, and said that it “became the inspiration for how a teacher could transform the life of a student”. While developing the character of a young boy based on Kurosawa, Bhatia and Gupte explored some possible reasons why he failed in school. Their research led them to the Maharashtra Dyslexia Association and Parents for a Better Curriculum for the Child (PACE). Dyslexia eventually became the central topic and theme of the film. The pair worked with dyslexic children to research and develop the screenplay, basing characters and situations on their observations. Bhatia and Gupte carefully concealed the children’s identities in the final version of the script. “While Amole has written what I think is a brilliant and moving script, his contribution towards the film is not limited to that of a writer. The entire pre-production was done by him including the most important task of creating the music … he has been present on set throughout the shooting as the Creative Director, and has been a big support and strong guiding force in my debut as a director. I thank him for that, and more so for having the faith in me by entrusting to me something that is so close to him.” Khan and Gupte first met in college. Khan has said that he admired Gupte’s abilities as an actor, writer, and painter. Three years before the film’s release, Gupte brought Khan to the project as a producer and actor. Gupte himself was to direct, but the first week’s were a great disappointment to Khan, who “lost faith in Amole and his capability of translating on screen what he had so beautifully written on paper”. Khan was on the verge of withdrawing his participation in the film because of these “creative differences”, but Gupte kept him on board by stepping down as director. Contrary to Khan’s claim, Gupte lashed out saying that after the wrap-up party, Khan announced that he was the director of the film, despite Gupte acting as director. Had it been necessary to hire a third party, production would have been postponed for 6–8 months as the new director prepared for the film. Keen to keep Safary as Ishaan—the actor might have aged too much for the part had production been delayed—Khan took over the role of director. was Khan’s first experience in the dual role of actor and director. He has admitted that the transition was challenging, stating that while he had always wanted to direct a film, it was unknown territory for him. Gupte remained on set, “guiding [Khan] and, at times, even correcting [him]”. Initially, the film was to retain the short story’s title of “High Jump”, which referenced Ishaan’s inability to achieve the in gym class. This subplot, which was filmed but later cut, would have tied into the original ending for the movie. In this planned ending, a “ghost image” separates from Ishaan after the art competition and runs to the sports field; the film would end on a freeze frame of Ishaan’s “ghost image” successfully making the leap. Aamir Khan disliked this proposed ending and convinced Gupte to rewrite it. With the working title no longer relevant, Khan, Gupte, and Bhatia discussed several alternatives, eventually deciding on Possible translations of this title include and . According to Khan: is a film about children and it is a film which celebrates the abilities of children. is a title which denotes that aspect. It is a title with a very positive feel to it. All the kids are special and wonderful. They are like stars on earth. This particular aspect gave birth to the title. Principal photography took place in India over five months. Khan spent his first two days as director the first scene to be filmed: Ishaan returning home from school and putting away his recently collected fish. Believing the audience should not be aware of the camera, he chose a simple shooting style that involved relatively little . The opening scene of Ishaan collecting fish outside his school was shot on location and at . The shots of Ishaan took place at the former, while those involving the gutter were filmed at a water tank at the latter. The tank’s water often became murky, forcing production to constantly empty and refill it, and causing the scene to take eight hours to film. The film’s next sequence involved Ishaan playing with two dogs. To compensate for the “absolutely petrified” Safary, most joint shots used a body double, though other portions integrated close-up shots of the actor. Ishaan’s nightmare—he becomes separated from his mother at a train station and she departs on a train while he is trapped in a crowd—was filmed in Mumbai on a permanent railway-station set. To work around the train set piece’s immobility, production placed the camera on a moving trolley to create the illusion of a departing train. For the sequences related from the mother’s point of view—shot from behind the actress—Chopra stood on a trolley next to a recreated section of the train’s door. All the school sequences were filmed on location. The production team searched for a Mumbai school with an “oppressive” feel to establish the “heaviness of being in a metropolitan school”, and eventually chose . As the school is situated along a main road filming took place on weekends, to minimise the background noise, but an early scene in which Ishaan is sent out of the classroom was filmed on the day of the . The production staff placed acrylic sheets invisible to the naked eye on the classroom windows to mask the sounds of nearby crowds and helicopters. served as Ishaan’s boarding school. The change of setting was a “breath of fresh air” for the production crew, who moved from Ishaan’s small house in Mysore Colony, to the “vast, beautiful environs” of . Production relied on for the brief scene of a bird feeding its babies. Khan carefully selected a clip to his liking, but learned three weeks before the film’s release that the footage was not available in the proper format. With three days to replace it or else risk delaying the release, Khan made do with what he could find. He says that he “cringes” every time he sees it. Real schoolchildren participated throughout the movie’s filming. Khan credited them with the film’s success, and was reportedly very popular with them. Furthermore, Khan placed a high priority on the day-to-day needs of his child actors, and went to great lengths to attend to them. The production staff made sure that the students were never idle, and always kept them occupied outside of filming. New Era Faculty Coordinator Douglas Lee thought the experience not only helped the children to learn patience and co-operation, but also gave them a better understanding of how they should behave towards children like Ishaan who have problems in school. Because filming at New Era High School occurred during the winter holiday, those portraying Ishaan’s classmates gave up their vacation to participate. To fill in the campus background, students from nearby schools were also brought in. A total of 1,500 children were used for wide-shots of the film’s art-fair climax; medium shots only required 400 students. New to acting, the children often made errors such as staring into the camera, and Khan resorted to unorthodox methods to work around their rookie mistakes. For example, an early scene in the film featured a school assembly; Khan wanted the students to act naturally and to ignore the principal’s speech, but recognised that this would be a difficult feat with cameras present. First Assistant Director Sunil Pandey spoke continuously in an attempt to “bore the hell out of [them]”, and they eventually lost interest in the filming and behaved normally. A later scene involved Nikumbh enlightening his class about famous people with dyslexia, and the children’s responses to his speech were the last portion to be filmed. Having already spent 3–4 days hearing the dialogue the children’s reactions were “jaded”. Khan opted to film them while he recited a tale, and manipulated his storytelling to achieve the varying spontaneous reactions. The following scene had the children playing around a nearby pond. Horrified when he learned that the water was 15 feet (4.6 m) deep, Khan recruited four lifeguards in case a child fell in. Khan found it important that the audience connect the film to real children, and had Pandey travel throughout India filming documentary-style footage of children from all walks of life. Those visuals were integrated into the end credits. While has been used in Indian television commercials, the film’s title sequence—a representation of Ishaan’s imagination —marked its first instance in a Bollywood film. Khan gave claymation artist Dhimant Vyas free rein over the various elements. The storyboarding took one and a half months and the shooting required 15 days. The “3 into 9” sequence, in which Ishaan delves into his imagination to solve a math problem, was originally conceived as a 3D animation. Halfway through its creation, however, Khan felt it was not turning out as he had envisioned it. Khan scrapped the project and hired Vaibhav Kumaresh, who hand-drew the scene as a 2D animation. Artist composed Ishaan and Nikumbh’s art-fair watercolor paintings. He held a workshop with the schoolchildren, and incorporated elements from their artwork into Ishaan’s. Mondal also instructed Khan on a painter’s typical mannerisms and movements. Gupte created the rest of Ishaan’s artwork and Assistant Art Director Veer Nanavati drew Ishaan’s flipbook. The art department’s designs for Ishaan’s school notebooks disappointed Khan, who had familiarized himself with dyslexic writing. Using his left hand, Khan instead wrote it himself. The musical sequence of “Jame Raho” establishes the characters of the four members of Ishaan’s family; for example, the father is hardworking and responsible, and Yohaan is an “ideal son” who does all the right things. A robotic style of music overlaps most of the sequence—this is mirrored by the machine-like morning routines of the mother, father, and Yohaan—but changes for Ishaan’s portion to imply that he is different from the rest. This concept is furthered by and having the camera sway with the music to create a distinct style. The twilight scenes of “Maa” were a particular issue for the production crew. Because the specific lighting only lasted ten to fifteen minutes a day, the scenes took nearly ten evenings to film. Production at one time considered having a child singing, but ultimately deemed it too over the top and felt it would connect to more people if sung by an adult. Shankar initially performed the song as a sample—they planned to replace him with another singer—but production eventually decided that his rendition was best. Ishaan’s truancy scene—he leaves school one day after realizing that his mother has not signed his failed math test—originally coincided with the song “Kholo Kholo,” but Khan did not believe it worked well for the situation. In his opinion, the accompanying song should focus on what a child wants—to be free—and be told from the first-person perspective instead of “Kholo Kholo ‘s second person. When Khan took over as director, he opted to use “Mera Jahan”—a song written by Gupte—and moved “Kholo Kholo” to the art fair. Viewers of test screenings were divided over the truancy scene. Half thoroughly enjoyed it but the rest complained that it was too long, did not make sense, and merely showed “touristy” visuals of Mumbai. Khan nevertheless kept the scene, because he “connected deeply” with it and felt that it established Ishaan’s world. choreographed the dance sequence of “Bum Bum Bole,” and was given free rein over its design. He had intended to use 40 students from his dance school, but Khan did not want trained dancers. Davar gave the children certain cues and a general idea of what to do, but left the style and final product up to them to avoid a choreographed appearance. Time constraints meant that while Khan was busy filming “Bum Bum Bole,” took over as director for “Bheja Kum”. The latter sequence, containing a “fun-filled” song of rhythmic dialogue, allowed the audience to perceive how Ishaan sees the world and written languages. It was intended to represent “a young boy’s worst nightmare, in terms of … the worst thing that he can think of”; Madhvani based the visual concept on his son’s fear of “creepy-crawlies” such as cockroaches, dragonflies, and lizards. ‘s made the creatures out of the English alphabet and numbers, although Khan insisted they include the Hindi alphabet as not all the audience would be familiar with English. The chalkboard writing’s transformation into a snake was included to surprise the audience and “end the song on a high note.” In writing the song “Taare Zameen Par,” lyricist followed the theme of “however much you talk about children, it’s not enough.” Every line throughout the song describes children, and only one repeats: “Kho Naa Jaaye Yeh / Taare Zameen Par” (“Let us not lose these / Little stars on earth”). The song is mostly set to the annual day performance by the developmentally disabled children of Tulips School. Actual students from Tulips School and Saraswati Mandir participated, and were filmed over a period of five days. The sequence originally featured numerous dance performances, but was trimmed down when test audiences found it too long. A song accompanying the scene in which Ishaan’s mother is watching home videos of her son was also cut, and replaced with background music after test audiences expressed their opposition to yet another song. Timing and other aspects are usually planned when scoring a film, but Khan chose to take a more improvised approach. Instead of using a studio, he and the trio recorded it at Khan’s home in Panchgani, to clear their heads and not be in the mindset of the city. As they watched the film, Khan pointed out when he wanted music to begin and of what type. Ehsaan Noorani noted that this strategy allowed the score to have a “spontaneity to it.” Different styles of background music were used to convey certain things. For example, a guitar is played when Ishaan is tense or upset, sometimes with discordant notes. The music of the opening scene—the recurring “Ishaan’s Theme,” which represents the character’s peace of mind—overpowers the background noise to show that Ishaan is lost in his own world; the noise becomes louder after he snaps back to reality. But the scene in which Nikumbh explains dyslexia to Ishaan’s family took the opposite approach. Silent at first, the music is slowly introduced as the father begins to understand his son’s dilemma. The almost seven-minute long scene scarcely used any background music, to slow the pace and make it seem more realistic. When filming part of the montage that details Ishaan’s tutoring by Nikumbh, Khan immediately decided it would be the “key art of the film”. He noted that “this one shot tells you the entire story”, and used it for the poster. The soundtrack for was released on 5 November 2007 under the label . The music is mainly composed by , with lyrics by . However, “Mera Jahan” was scored by Shailendra Barve and written by Gupte. The Indian trade website reported that the album sold around 1,100,000 units, becoming the year’s thirteenth highest-selling. Joshi received the , and won the , both for “Maa.” was released worldwide on 14 December 2007, although countries such as Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Fiji opened it on 20 December. It debuted in India with 425 prints, although revenue-sharing issues between the film’s distributors and theatre owners caused some slight delays. The movie grossed (US$3.63 million) domestically within the first three days. Its theatre occupancy in Mumbai dropped to 58 percent during its third week, but climbed back to 62 percent the following week—this brought the total to (US$18.62 million)—after the government granted the film exemption from the . Anticipating further tax exemption in other states, world distributor circulated 200 more prints of the film. The film completed its domestic run with $19,779,215. To reach more audiences, the film was later dubbed in the regional languages of (Vaal Nakshatram) and . Both were scheduled for release on 12 September 2008. It grossed $1,223,869 in the US by its seventh week, and £351,303 in the UK by its ninth week. Reports regarding the film’s worldwide gross have conflicted, with sources citing (US$21.52 million), (US$23.82 million) (US$25.88 million), (US$31.68 million), and (US$32.65 million). In response to Khan’s support for the and his criticism of Chief Minister , approximately 50 activists of the Group conducted protests outside of PVR and theatres in , . The group also issued statements to all the multiplexes of Gujarat, suggesting that the film not be screened unless Khan apologised for his comments. The INOX cinema eventually the film; INOX Operations Manager Pushpendra Singh Rathod stated that “INOX is with Gujarat, and not isolated from it”. The screened on 29 October 2008 in . Khan noted in his official blog that there were about 200 people in the audience and that he was “curious to see the response of a non-Indian audience to what we had made.” He felt some concern that was shown in a conference room rather than a cinema hall and was projected as a DVD rather than as a film. He said that the showing concluded to an “absolutely thunderous standing ovation” which “overwhelmed” him and that he “saw the tears streaming down the cheeks of the audience.” Khan also noted that the reaction to the film “was exactly as it had been with audiences back home in India”. released the film on DVD in India on 25 July 2008. It was launched at Darsheel Safary’s school, Green Lawns High School, in Mumbai. Aamir Khan, Tisca Chopra, Vipin Sharma, Sachet Engineer, and the rest of the cast and crew were present. In his speech, Khan stated, “Darsheel is a very happy child, full of life and vibrant. I am sure it’s because of the way his parents and teachers have treated him. I must say Darsheel’s principal Mrs. Bajaj has been extremely supportive and encouraging. The true test of any school is how happy the kids are and by the looks of it, the children here seem really happy.” , whose parent company previously acquired 33 percent of UTV Software Communications, bought the DVD rights for distribution in North America, the United Kingdom, and Australia for (US$830,000). This marked “the first time an international studio has bought the video rights of an Indian film.” Retitling it , Disney released the film in 2 on 26 October 2009, in Region 1 on 12 January 2010, and in Region 4 on 29 March 2010. A three-disc set, the Disney version features the original Hindi audio soundtrack with English subtitles or another dubbed in English, as well as bonus material such as audio commentary, deleted scenes, and the musical soundtrack. The film is available on . received widespread critical acclaim upon release. On the website , 93% of 14 critics’ reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.4/10. Subhash K. Jha suggests that the film is “a work of art, a water painting where the colors drip into our hearts, which could easily have fallen into the motions of over-sentimentality. Aamir Khan holds back where he could easily resort to an extravagant display of drama and emotions.” of wrote that Khan “rekindles those uncomfortable moments of our childhood but reassures us that hey, it’s quite okay to be out-of-the-box,” and labelled the movie “a must-experience for sensitive viewers.” of called it “the movie of the year,” writing that “the filmmaking here is calculatedly flawed because it is all-heart. While it is world-class in terms of sensibility, craft and performances (almost), it does feel the need to reach out, please and educate a mass.” of argued that the true power of the film lies in its “remarkable, rooted, rock-solid script which provides the landscape for such an emotionally engaging, heart-warming experience.” Manish Gajjar from the stated that the film “touches your heart and moves you deeply with its sterling performances. [It is] a film full of substance!” Jaspreet Pandohar, also of BBC, posited that is a “far cry from the formulaic masala flicks churned out by the Bollywood machine,” and is “an inspirational story that is as emotive as it is entertaining; this is a little twinkling star of a movie.” Furthermore, Aprajita Anil of gave the film four stars and stated, ” cannot be missed. Because it is different. Because it is delightful. Because it would make everyone think. Because it would help everyone grow. Because very rarely do performances get so gripping. And of course because the ‘perfectionist’ actor has shaped into a ‘perfectionist’ director.” In addition, filmmaker stated that, ” took me back to my hostel days. If you take away the dyslexia, it seems like my story. The film affected me so deeply that I was almost left speechless. After watching the , I was asked how I liked I could not talk as I was deeply overwhelmed.” However, there were some criticisms. Jha’s only objection to the film was Nikumbh’s “sanctimonious lecture” to Ishaan’s “rather theatrically-played” father. Jha found this a jarring “deviation from the delectable delicacy” of the film’s tone. Although she applauded the film overall and recommended “a mandatory viewing for all schools and all parents”, of believed the second half was “a bit repetitive,” the script needed “taut editing,” and Ishaan’s trauma “[seemed] a shade too prolonged and the treatment simplistic.” Despite commending the “great performances” and excellent directing, Gautaman Bhaskaran of , too, suggested that the movie “suffers from a weak script.” Likewise, Derek Kelly of criticized it for what he described as its “touchy-feely-ness” attention to “a kid’s plight.” Kelly also disliked the film for being “so resolutely caring … and devoid of real drama and interesting characters” that “it should have ‘approved by the Dyslexia Assn.’ stamped on the posters.” The core plot of the movie was reported to be similar to the 1985 American movie . In his article ” and dyslexic savants” featured in the , Ambar Chakravarty noted the general accuracy of Ishaan’s dyslexia. Though Chakravarty was puzzled by Ishaan’s trouble in simple arithmetic—a trait of rather than dyslexia—he reasoned it was meant to “enhance the image of [Ishaan’s] helplessness and disability”. Labeling Ishaan an example of “dyslexic savant syndrome”, he especially praised the growth of Ishaan’s artistic talents after receiving help and support from Nikumbh, and deemed it the “most important (and joyous) neurocognitive phenomenon” of the film. This improvement highlights cosmetic neurology, a “major and therapeutically important issue” in and . Likewise, in their article “Wake up call from ‘Stars on the Ground'” for the , T. S. Sathyanarayana Rao and V. S. T. Krishna wrote that the film “deserves to be vastly appreciated as an earnest endeavor to portray with sensitivity and empathetically diagnose a malady in human life”. They also felt it blended “modern professional knowledge” with a “humane approach” in working with a dyslexic child. However, the authors believed the film expands beyond disabilities and explores the “present age where everyone is in a restless hurry”. The pair wrote, “This film raises serious questions on mental health perspectives. We seem to be heading to a state of mass scale mindlessness even as children are being pushed to ‘perform’. Are we seriously getting engrossed in the race of ‘achievement’ and blissfully becoming numb to the crux of life i.e., experiencing meaningful living in a broader frame rather than merely existing?” The film depicts how “threats and coercion are not capable of unearthing rich human potentialities deeply embedded in children”, and that teachers should instead map their strengths and weakness. With this in mind, the author felt that Khan “dexterously drives home the precise point that our first priority ought to be getting to know the child before making any efforts to fill them with knowledge and abilities”. Overall, the pair found a “naive oversimplification” in the film. With India “only recently waking to recognizing the reality and tragedy of learning disability”, however, they “easily [forgave the film’s fault] under artistic license”. The film raised awareness of the issue of dyslexia, and prompted more open discussions among parents, schools, activists, and policymakers.<br />

Anjuli Bawa, a parent-activist and founder of Action Dyslexia Delhi, said that the number of parents who visit her office increased tenfold in the months following the film’s release. Many began taking a more proactive approach by contacting her after noticing problems, rather than using her as a last resort. Gupte himself received “many painful letters and phone calls” from Indian parents. He noted, “Fathers weep on the phone and say they saw the film and realized that they have been wrong in the way they treated their children. This is catharsis.” These reactions have also brought about a change in policies. The film, only ten days after its debut, influenced the to provide extra time to disabled children—including visually impaired, physically disabled, and dyslexic students—during exams. In 2008, Mumbai’s civic body also opened 12 classrooms for autistic students. In , the education administration started a course to educate teachers on how to support children with learning disabilities. The film has had a similarly positive response in , where the film was not officially released yet has a large online cult following due to Aamir Khan’s popularity in the region after the success of (2009). The film has been well received by Chinese audiences for how it tackles issues such as education and dyslexia, and is one of the highest-rated films on popular Chinese film site , along with two other Aamir Khan films, and (2016). In 2025, a spiritual sequel titled was announced. Directed by R.S. Prasanna and produced by Aamir Khan and Aparna Purohit, the film features Khan alongside and a cast of ten newcomers. Unlike its predecessor, which focused on , centers around a basketball coach who trains a team of players with intellectual disabilities, and is an official remake of 2018 Spanish film . Sitaare Zameen Par was theatrically released on 20 June 2025. Among its many awards, won the for 2008, as well as the . Khan’s directorial role and Safary’s performance were recognized at the 2008 Zee Cine Awards, 2008 Filmfare Awards, and 4th Apsara Film & Television Producers Guild Awards. was initially acclaimed as India’s official entry for the 2009 , but after it failed to progress to the short list, a debate began in the Indian media as to why Indian films never win Academy Awards. Speculation for the reasons behind s failed bid included ‘s Arthur J. Pai’s observation that it lacked mainstream media attention; AMPAS jury member Krishna Shah criticized its length and abundance of songs. “Three days before hit theaters in the U.S. and India, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its shortlist of nine films edging closer to a foreign-language nomination. India’s submission, the powerful and moving by Aamir Khan, didn’t make the cut. Sadly, that film never will be seen by mainstream American audiences; yet is enjoying a hefty publicity push. If only could have gotten its hands on that magic potato.” Khan claimed that he was “not surprised” that was not included in the Academy Award shortlist, and argued, “I don’t make films for awards. I make films for the audience. The audience, for which I have made the film, really loved it and the audiences outside India have also loved it. What I am trying to say is that film has been well loved across the globe and that for me it is extremely heartening and something that I give very high value to.” The Indian news media also frequently compared nomination failure with the British drama film s multiple Academy Award nominations and wins, and noted that other Indian films in the past were overlooked. Film critic argued that it is difficult to compare the two films and noted that was being marketed in a way that Indian films such as could not compete with. In this context, actor stated, “I</p>

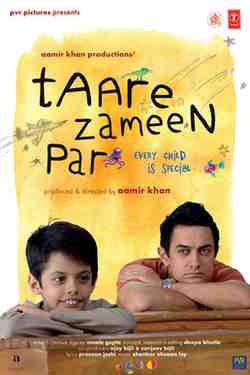

Details

🎬

Genres:

✍️

Writer:

Amole Gupte

👤

Producer:

Aamir Khan

🎵

Music:

🎬

Director:

📸

Cinematography:

Satyajit Pande, (Setu)

👥

Starring:

0

📅

Release Date:

21-Dec-07

✂️

Edited By:

Deepa Bhatia

💸

Budget:

12

🏭

Production Company:

📺

OTT Platform:

Netflix

⏱️

Runtime:

2h 44m

🗣️

Language:

Hindi

💵

Box Office:

98.48

🌐

Other Languages:

📄

Screenplay:

🔒

Censorship:

Reviews

There are no reviews yet. Be the first one to write one.